Andrew Valentine

Machine Learning

The term ‘machine learning’ encompasses a wide variety of different methods and approaches, based around the idea that ‘interesting’ or ‘useful’ relationships can be inferred from examples, rather than needing to be explicitly defined by a mathematical or computational model. Much of my work involves translating and adapting concepts from the machine learning literature to suit the specific needs of geoscience questions.

I wrote an introduction to machine learning aimed at the geomorphology community.1

Contents

Deep Learning

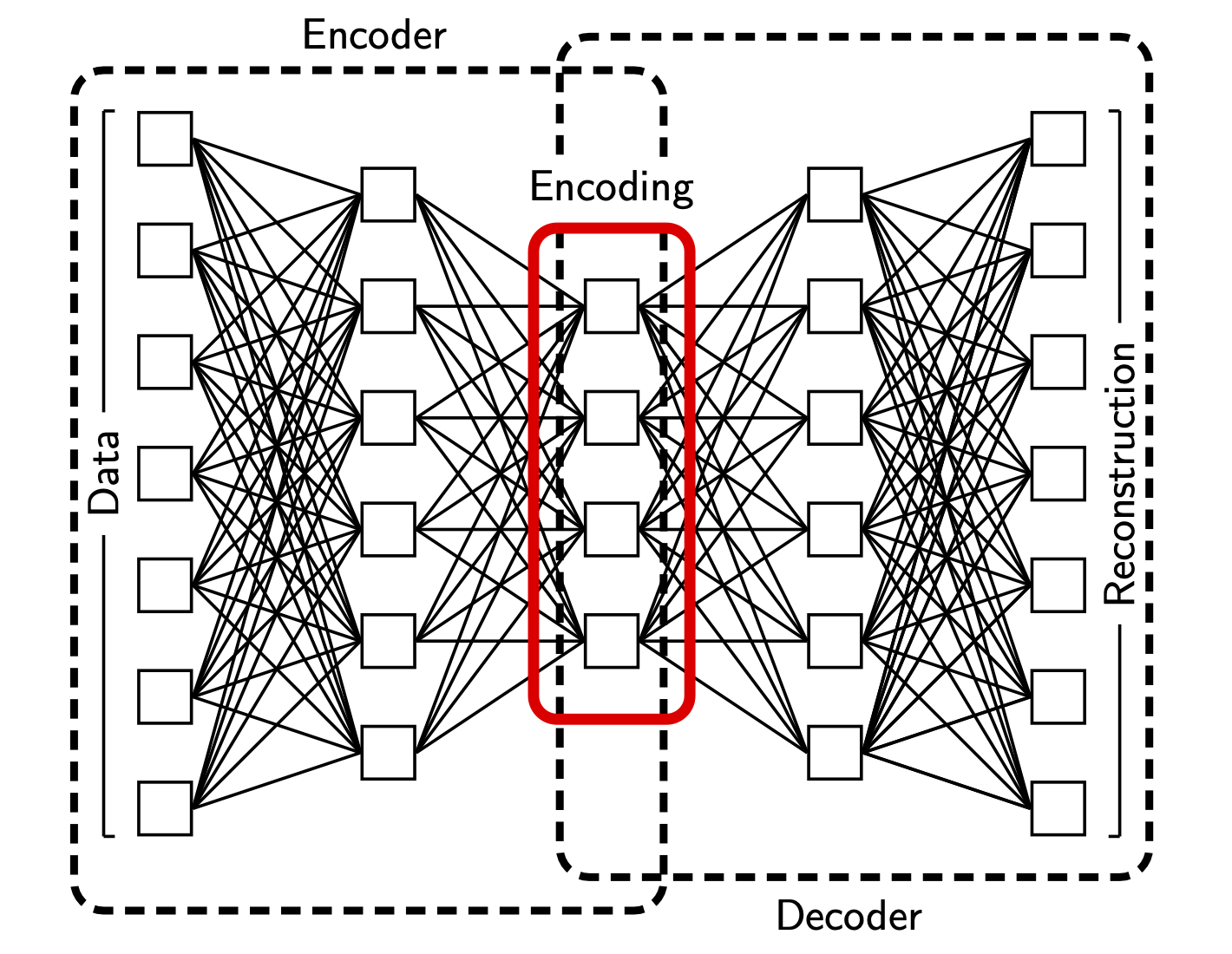

I developed some of the first applications of deep learning in geophysics. A paper by Hinton & Salukhutdinov had introduced the concept of an ‘autoencoder’, which Jeannot Trampert and I found interesting. Back in 2011, easy-to-use machine learning frameworks such as PyTorch and Tensorflow weren’t available, so I wrote a fairly extensive autoencoder package in C and we set about exploring how it performed for seismic waveforms.2 However, we lacked some key insights that came later (or at least, had not achieved full recognition in 2011): convolutional layers, ReLU activations, and GPU-enabled training at scale.

Schematic of an autoencoder network.2

We went on to explore the use of autoencoders for preprocessing seismic data prior to inversion (unpublished; see Chapter 8 of Ralph de Wit’s PhD thesis), and they became part of the workflow Suzanne Atkins developed for geodynamic inference.3 I also used them to develop an automated data-processing framework for geomorphology – see below.

More recently I have worked with Charles Le Losq on using deep neural networks to infer physical properties of molten glass.4

Data processing

Seismogram quality control

A classic application of machine learning is to support data processing, particularly for tasks that are difficult to fully quantify and traditionally rely on the intuition of an experienced analyst. During my PhD, I developed a neural network framework for performing quality assessment of long-period seismograms recorded at teleseismic distances.5 This aimed to automate basic quality control tasks, using a simplified representation of the spectral properties of ‘good’ and ‘unusable’ data selected by the operator. A Python/Tkinter GUI – unfortunately now lost – allowed the user to classify data and train the network in an ‘online’ mode; this was my first major Python project. We later re-implemented the quality assessment task in the time domain using the autoencoder.2

Finding seamounts

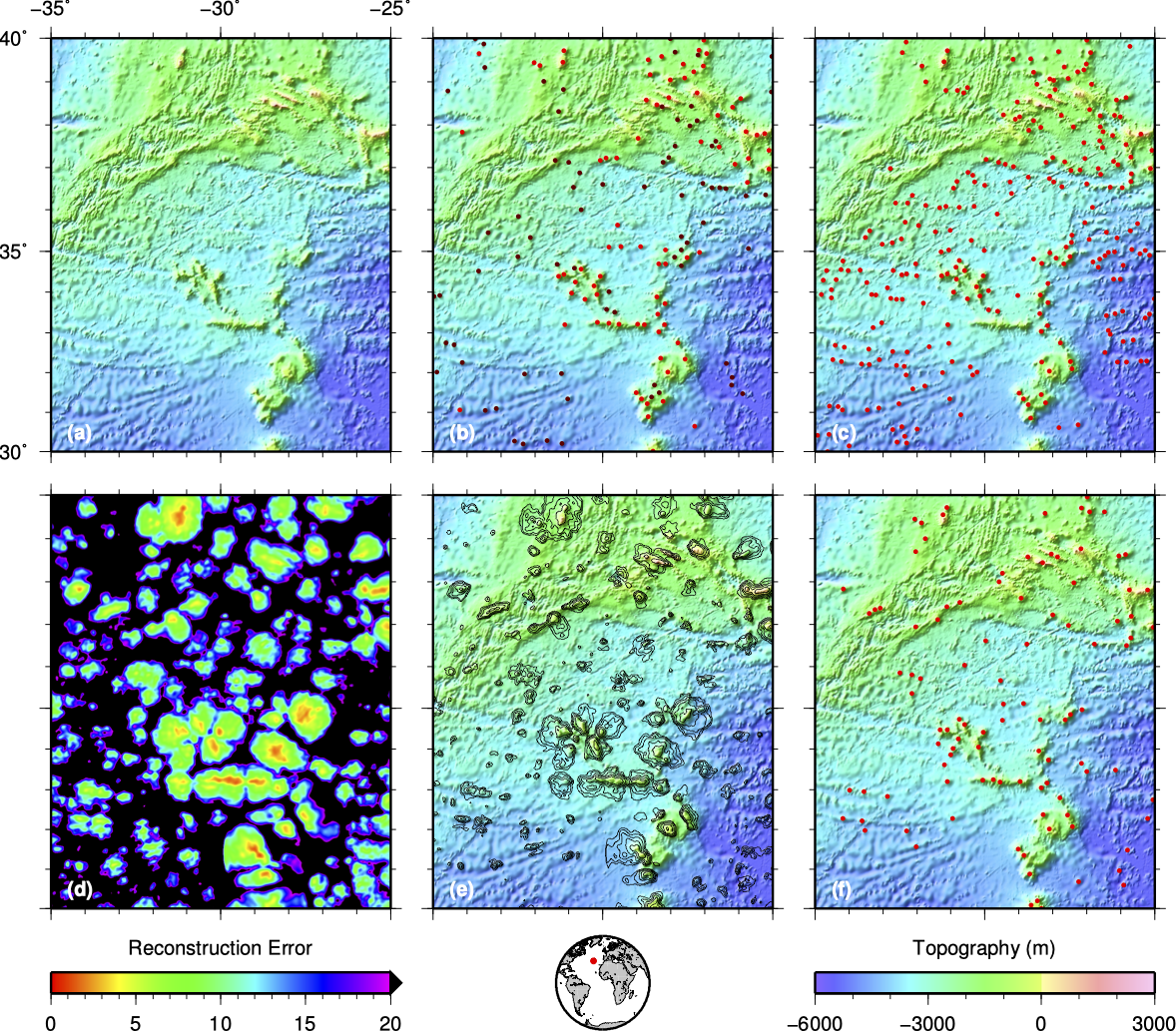

Seamounts in the Atlantic Ocean – detected using an autoencoder. 6

Seamounts in the Atlantic Ocean – detected using an autoencoder. 6

We know surprisingly little about the world’s oceans. One fairly open question concerns the number and distribution – spatially, temporally and by size – of seamounts, or underwater volcanoes. Topographic maps of the sea floor have variable resolution, generally being inferred from satellite gravity measurements, combined with whatever direct observations (e.g. SONAR) happen to be available. Seamounts (or at least, large seamounts) are fairly easy to detect visually in these maps, but the scale of the oceans makes comprehensive visual classification unfeasible. Kim & Wessel had developed an automated detection algorithm that attempted to detect seamounts by modelling them as 2D Gaussians, but this simple model fails to capture the full range of features seen in real data. This seemed like an ideal task for a neural network – but using a conventional classifier was not straightforward, as it proved difficult to create a training set with a sufficiently-representative suite of ‘not seamounts’. We therefore developed a novel approach that used an autoencoder trained only on seamount-like topography.6 The result was a low-dimensional representation that performed well for seamounts (i.e. the training data could be accurately reconstructed), but poorly for everything else. Reconstruction error can therefore be used as to measure how well any site matches the characteristics of the training dataset, and hence automatically detect seamounts.

Prior sampling

I have worked extensively on the development of ‘prior sampling’ – a framework for tackling inverse problems using the tools of machine learning. See this page for more details.

Inverse theory

Many of my contributions to inverse theory have been supported or inspired by things I found in the machine learning literature. Examples include:

- Automatic regularisation – Learning in backpropagation networks, Mackay a & b.

- Probabilistic continuous inverse theory – Gaussian processes, e.g. Rasmussen & Williams.

Contents

Back to research overview

References

-

Valentine & Kalnins, 2016. An introduction to learning algorithms and potential applications in geomorphometry and earth surface dynamics. doi:10.5194/esurf-4-445-2016 ↩

-

Valentine & Trampert, 2012. Data space reduction, quality assessment and searching of seismograms: autoencoder networks for waveform data. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05429.x ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Atkins, Valentine, Tackley & Trampert, 2016. Using pattern recognition to infer parameters governing mantle convection. doi:10.1016/j.pepi.2016.05.016 ↩

-

Le Losq, Valentine, Mysen & Neuville, 2021. Structure and properties of alkali aluminosilicate glasses and melts: insights from deep learning. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2021.08.023 ↩

-

Valentine & Woodhouse, 2010. Approaches to automatic data selection for global seismic tomography. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2010.04658.x ↩

-

Valentine, Kalnins & Trampert, 2013. Discovery and analysis of topographic features using learning algorithms: A seamount case-study. doi:10.1002/grl.50615 ↩ ↩2