Andrew Valentine

Earthquakes

To many people, ‘seismology’ means ‘earthquakes’. Quite a bit of my work has focussed on how we can use seismic observables to obtain information about earthquakes, particularly in real-time settings for early warning.

Contents

Centroid–moment-tensor inversion

In global seismology, earthquake mechanisms are usually described by a centroid–moment-tensor (CMT) representation, which assigns the earthquake to a single point in space and time, and provides information about the focal mechanism. CMT solutions are routinely calculated by (e.g.) the Global CMT project, using a method based on the work of Dziewonski, Chou and Woodhouse.

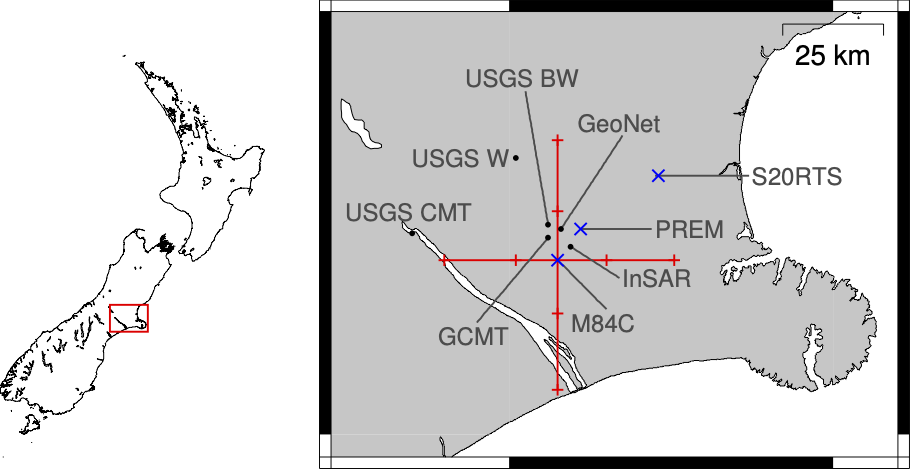

In order to determine CMT solutions, one needs to know something about earth structure. However, in order to make models of earth structure, we must use CMT solutions as inputs for seismic simulations. This circularity can be problematic, and my first paper demonstrated that there is potential for tomographic models to acquire an imprint of the structure that was used to obtain the CMT solutions.1 Addressing this is not too difficult conceptually – it requires simultaneous inversion for structure and all source information – but implementing this is harder. I was able to develop efficient algorithms that embed an implicit source update within the structural inversion, at comparatively low cost. I also made an attempt to quantify the true uncertainities on catalogue CMT parameters, taking the incompletely-known earth structure into account.2

GPS seismology

Traditional seismic instruments are accelerometers, recording very small motions of the Earth’s surface. While accurate and sensitive, they can also present challenges: they tend to be delicate, expensive to run and maintain, and a relatively narrow sensitivity band – an instrument designed to record distant earthquakes will be overwhelmed by the strength of ground shaking from nearby events. There was therefore considerable interest in how continuously-recording GPS stations could perform as seismometers, particularly for near-field monitoring of seismic zones. We demonstrated that it is possible to obtain CMT solutions from GPS data,3 and explored the feasibility of doing this in real-time settings.4

Earthquake early warning

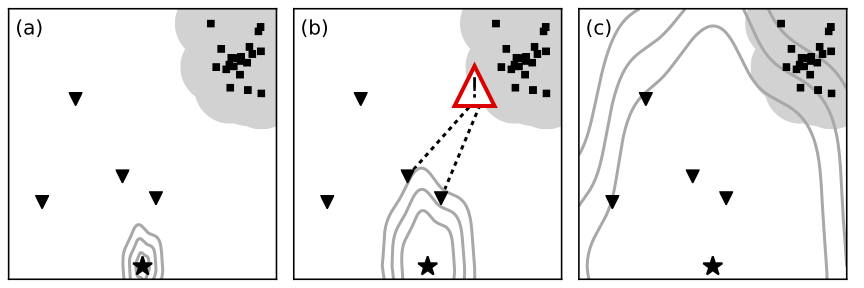

Real-time analysis is important because it enables earthquake early warning – rapid analysis of the first seismic signals coming from an earthquake, so that alerts can be sent out ahead of the wavefront. A few seconds’ warning is enough to take actions that mitigate the human and economic costs of the earthquake: machinery can be made safe, emergency generators can be started, and people can be warned to take cover. However, robust rapid analysis is a challenging problem. In particular, it is not feasible to run complex numerical simulations of wave propagation in the timeframe available. A number of studies had addressed this using approximate physics (sacrificing accuracy) or through vast pre-computed databases of synthetic seismograms.

We saw an opportunity to apply machine learning to the problem – in particular, the prior sampling technique that provides an efficient mechanism for storing and querying precomputed data. Paul Käufl systematically developed this concept, working up from simple datasets,5 through more complex physics,6 until he was able to demonstrate real-time earthquake early warning using physically-complete modelling.7

Contents

Back to research overview

References

-

Valentine & Woodhouse, 2010. Reducing errors in seismic tomography: Combined inversion for sources and structure. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04452.x. ↩

-

Valentine & Trampert, 2012. Assessing the uncertainties on seismic source parameters: Towards realistic error estimates for centroid-moment tensor determinations. doi:10.1016/j.pepi.2012.08.003 ↩

-

O’Toole, Valentine & Woodhouse, 2012. Centroid-moment tensor inversions using high-rate GPS waveforms. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2012.05608.x ↩

-

O’Toole, Valentine & Woodhouse, 2013. Earthquake source parameters from GPS-measured static displacements with potential for real-time application. doi:10.1029/2012GL054209 ↩

-

Käufl, Valentine, O’Toole & Trampert, 2014. A framework for fast probabilistic centroid–moment-tensor determination — Inversion of regional static displacement measurements. doi:10.1093/gji/ggt473 ↩

-

Käufl, Valentine, de Wit & Trampert, 2015. Robust and fast probabilistic source parameter estimation from near-field displacement waveforms using pattern recognition. doi:10.1785/0120150010 ↩

-

Käufl, Valentine & Trampert, 2016. Probabilistic point source inversion of strong-motion data in 3D media using pattern recognition: A case study for the 2008 Mw5.4 Chino Hills earthquake. doi:10.1002/2016GL069887 ↩