Andrew Valentine

From windows to volcanoes: How Pytorch is helping us understand glass

6 December 2021by Charles Le Losq, Andrew Valentine and Barbara Baldoni

This article first appeared in the Pytorch blog on medium.com.

Lava flow at the Piton de la Fournaise in April 2021. The rapid cooling of lava leads to the formation of volcanic glass. Copyrights OVPF-IPGP.

Lava flow at the Piton de la Fournaise in April 2021. The rapid cooling of lava leads to the formation of volcanic glass. Copyrights OVPF-IPGP.

Glass is everywhere around us. It lets light into your house, stores your food and drink, and decorates your home. It’s in the screen you are looking at right now; in next-generation batteries or medical implants; even in volcanoes. In fact, it’s one of the most important materials on our planet. It’s so important that Morse and Evenson proposed that we are living in the Glass Age. And by using deep learning with PyTorch, we can now understand glass better than ever before.

Machine learning and glass design

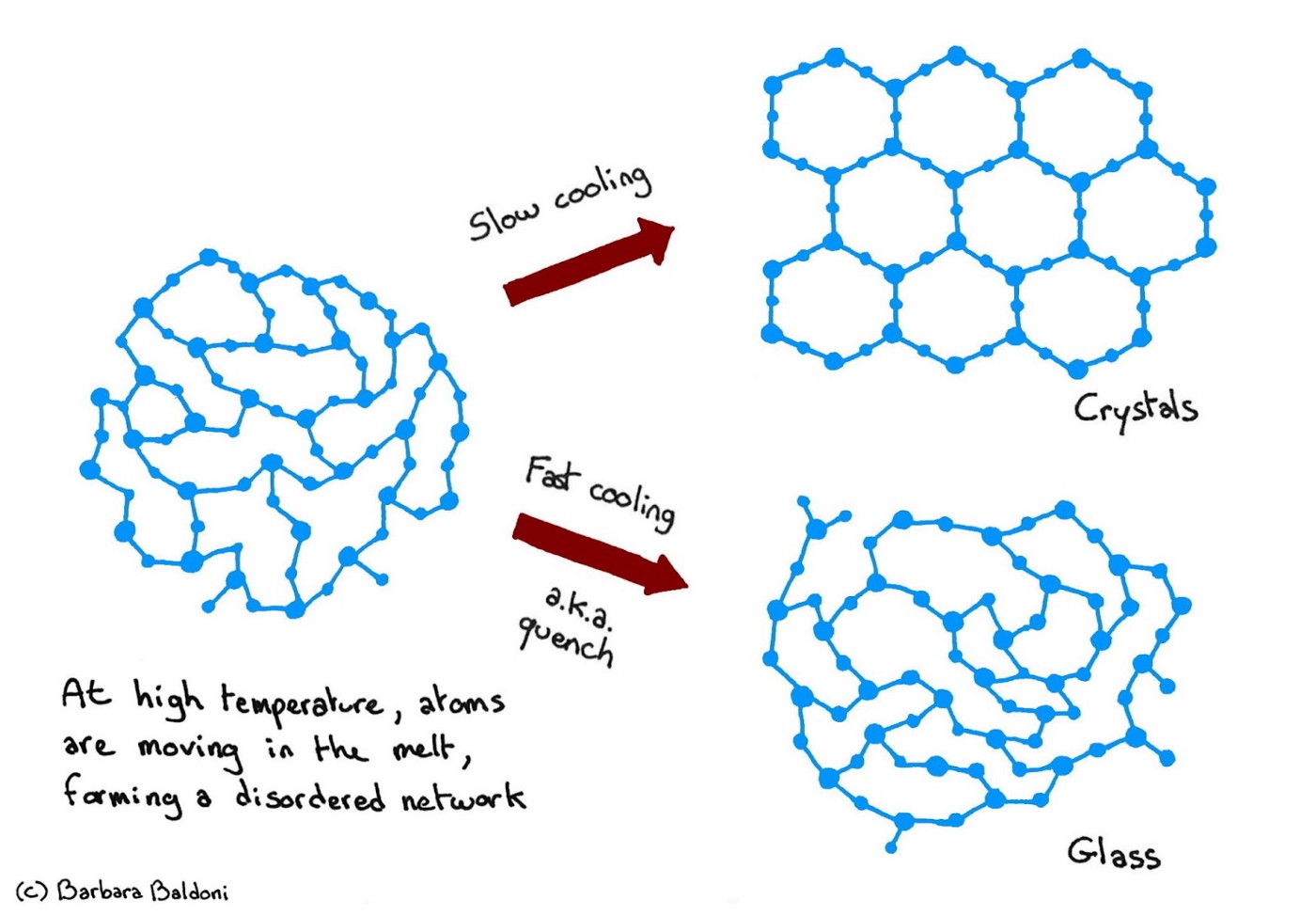

To make a glass, you need to melt something and then cool it very rapidly. In the molten liquid, atoms are disordered and move around freely. Normally, the process of solidification would involve the atoms reorganising into regular structures, known as crystals — but if the melt is cooled quickly enough, there isn’t time for this to occur. The result is a solid material that still has the atomic structure of a liquid: this is what we know as ‘glass’.

The structure of a glass is a frozen picture of that of its parental melt, with a disordered network of atoms (here a schematic network with two different types of atoms). Slow cooling allows rearrangements to occur, and usually leads to the formation of crystals with long-range atomic order.

The structure of a glass is a frozen picture of that of its parental melt, with a disordered network of atoms (here a schematic network with two different types of atoms). Slow cooling allows rearrangements to occur, and usually leads to the formation of crystals with long-range atomic order.

Not all glass is good for windows. It turns out that the physical properties of a glass depend on the chemical composition of the molten liquid we started with. By tweaking this composition, we can control the strength and transparency of the glass; how it reacts to chemicals; whether it conducts electricity. If we have a particular application in mind — perhaps a new smartphone screen — we can design a glass that meets our needs. However, this has always relied on an expensive and time-consuming process of experimentation, trial and error. Now, machine learning promises to revolutionise glass design.

i-Melt : a grey-box multitask model

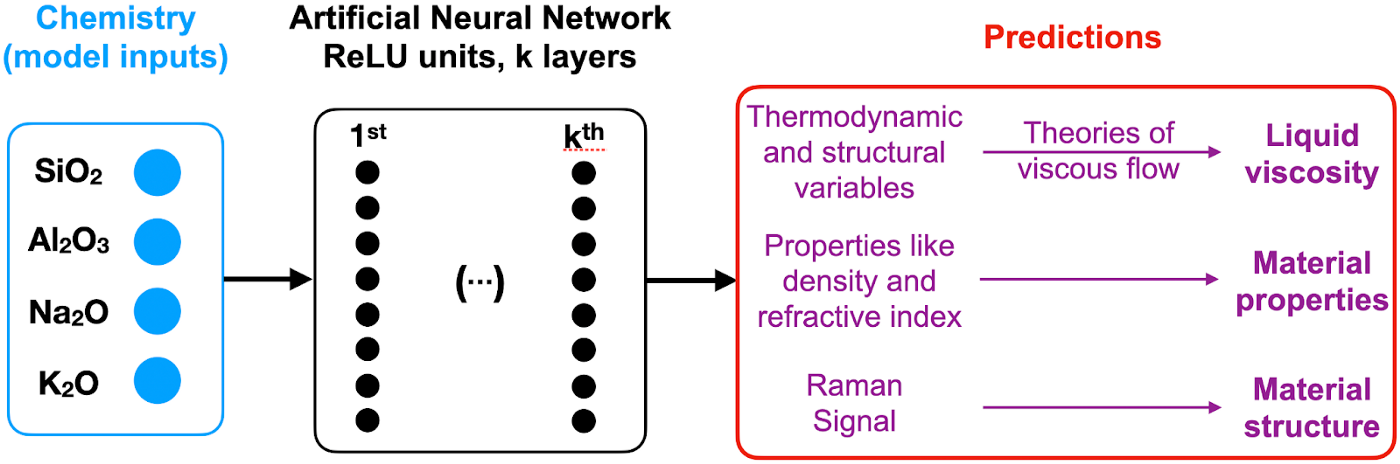

In a new work published in the journal Geochemica et Cosmochimica Acta, we present i-Melt — a physics- and chemistry-informed deep neural network which can accurately predict glass properties based on the composition of the melt. i-Melt is a grey-box model: it embeds known physical equations and thermodynamic principles alongside learned relationships to ensure meaningful and realistic results. So far, we have focused on a group of glasses known as ‘aluminosilicates’ (which just means their main ingredients are oxides of aluminum and silicon). These are very common in a variety of natural and industrial settings. We train i-Melt using a database of experimental observations across a variety of compositions, and obtain a model that can predict a wide range of properties including melt viscosity, glass density and optical refractive index, as well as glass Raman spectra (a measure of the atomic structure).

i-Melt is a serialized model that takes in input glass composition, passes it to a deep feed-forward neural network to predict latent and observed variables.

i-Melt is a serialized model that takes in input glass composition, passes it to a deep feed-forward neural network to predict latent and observed variables.

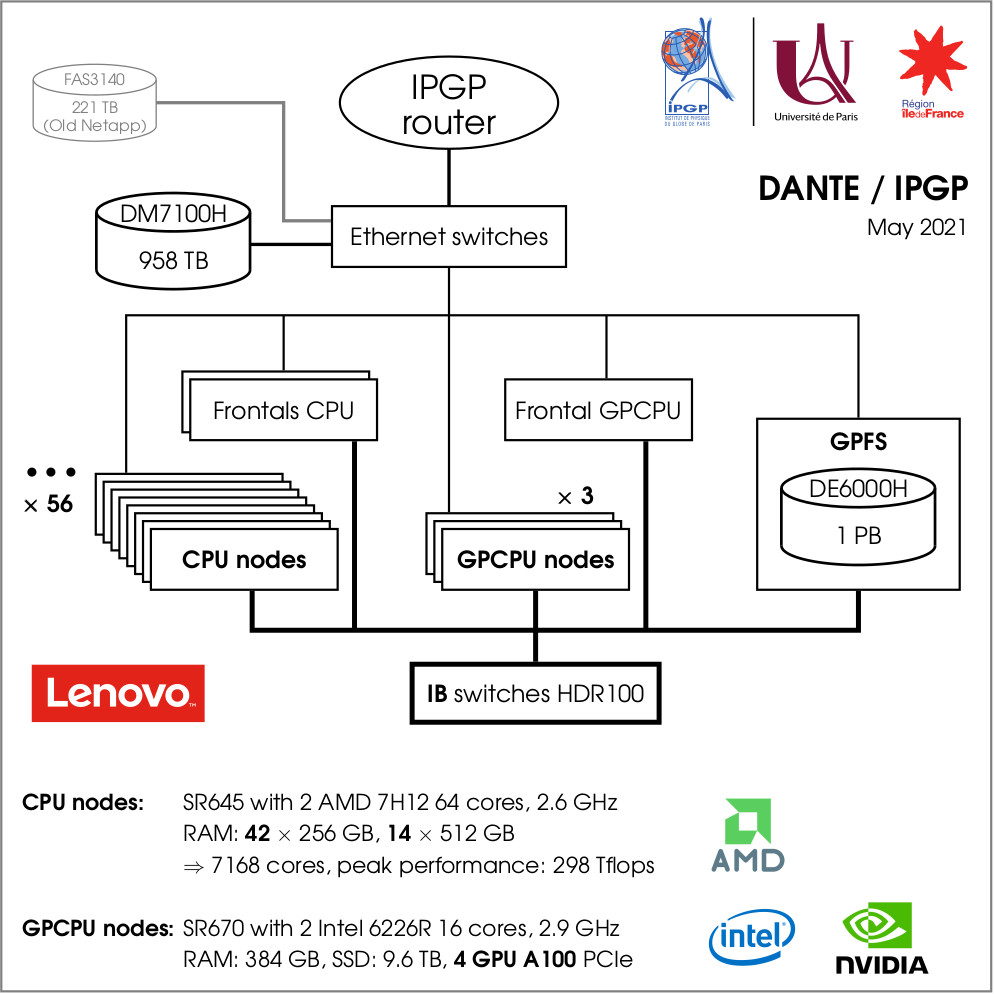

i-Melt is built using PyTorch, and the rich flexibility and power of the PyTorch framework are integral to its success. This made it straightforward to develop models that combine physical equations with machine learning, and to explore and test a range of different approaches. We also benefited from the ability to seamlessly switch between GPU and CPU-based computations, allowing us to exploit the new DANTE computational cluster at IPGP — University of Paris, equipped with A100 NVidia GPUs.

Schematics of the DANTE cluster at IPGP, University of Paris. Hyperparameter search and final training of i-Melt were performed using the A100 GPUs. Copyrights IPGP — University of Paris.

Schematics of the DANTE cluster at IPGP, University of Paris. Hyperparameter search and final training of i-Melt were performed using the A100 GPUs. Copyrights IPGP — University of Paris.

Model evaluation

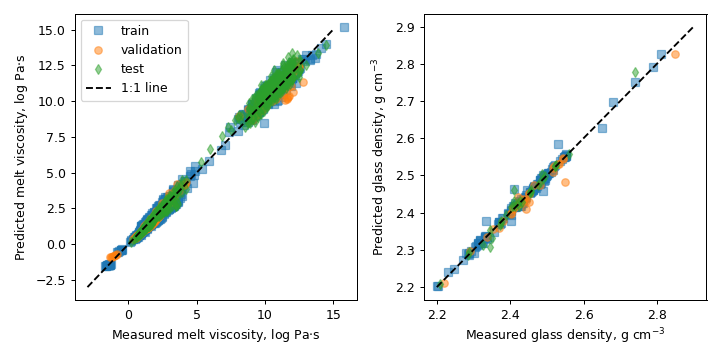

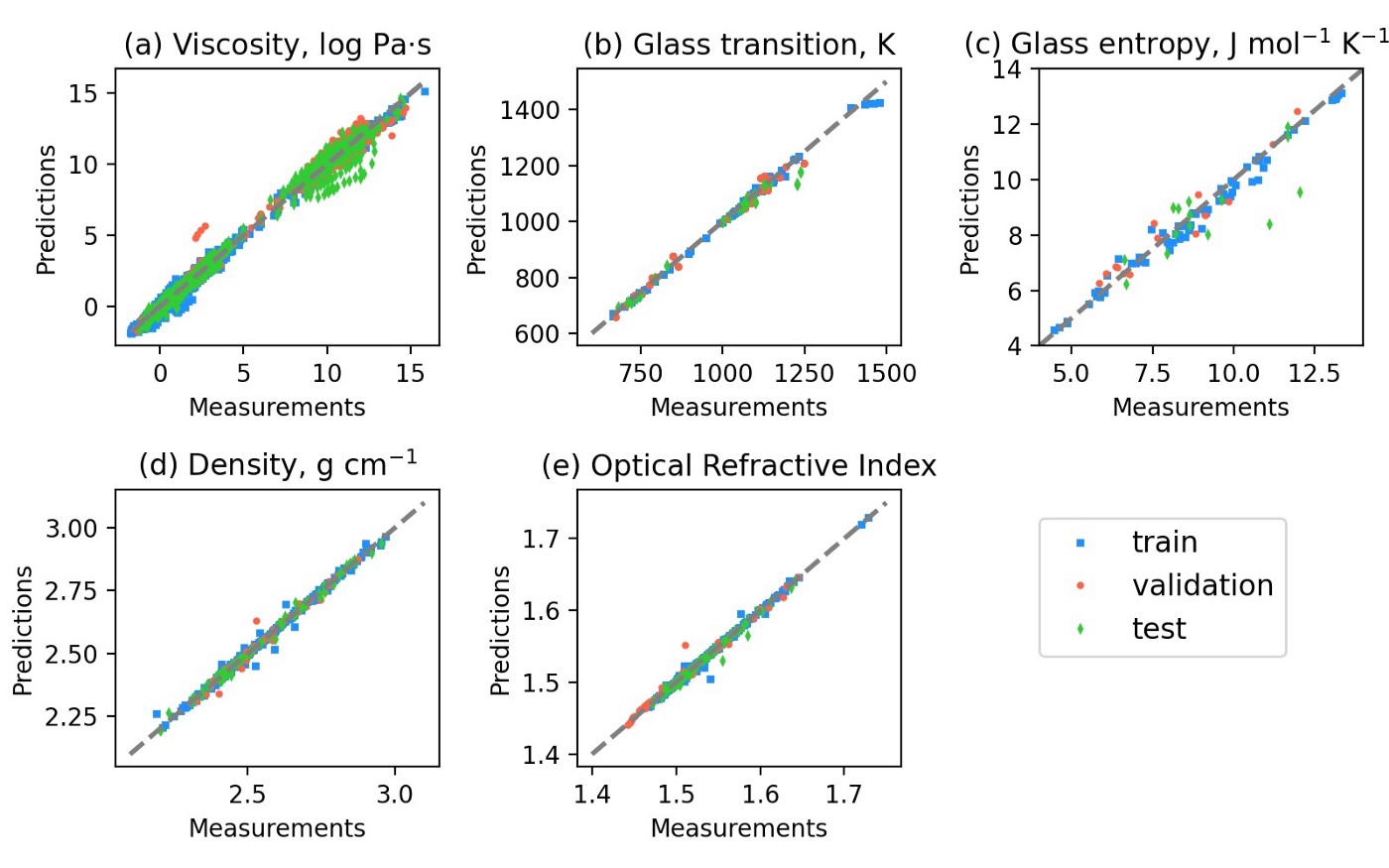

The i-Melt prototype focuses on glasses made from four ingredients: oxides of sodium, potassium, aluminium and silicon (specifically, Na₂O-K₂O-Al₂O₃-SiO₂ glasses). Within this system, the viscosity of molten glass varies considerably (from -2 to 14 log Paᐧs), and i-Melt successfully predicts this with a precision better than 0.4 log unit. Other properties are also well predicted, including the temperature at which the melt ‘freezes’ into a glass (the glass transition temperature; RMSE test: 19 K), the glass density (RMSE test: 0.02 g cm⁻³) and the optical refractive index (RMSE test: 0.006).

Predicted values with i-Melt versus measurements from the training, validation and testing datasets for viscosity of molten glasses on the left, and the density of glasses at room temperature on the right.

Predicted values with i-Melt versus measurements from the training, validation and testing datasets for viscosity of molten glasses on the left, and the density of glasses at room temperature on the right.

Use cases

i-Melt has a wide range of potential applications. First, it can be used to help engineer materials with particular properties, and optimize industrial processes. In fact, you can try this out for yourself using i-Melt’s online interface, powered by Streamlit, or using i-Melt as a library. For instance, we take a glass with 65 mol% SiO₂, 10 mol% Al₂O₃, 20 mol% Na₂O and 5 mol% K₂O, and see how its properties change change if we substitute 3 mol% Al₂O₃ by 3 mol% K₂O:

Running the code reveals that this small change in composition barely affects the optical refractive index — which determines the visual appearance of the glass — or its density. However, it significantly reduces the temperature at which the glass can be worked, which could allow manufacturers to reduce the operating temperature of their furnaces by around 10 %. This offers a route towards substantial savings on both energy costs, and CO₂ emissions. Of course, the current version of i-Melt only includes a small number of ‘ingredients’, but future developments will enable us to make calculations for more complex glass compositions (see Perspectives below).

We can also use i-Melt to understand volcanoes. Some volcanic eruptions are violently explosive, such as Mt St Helens (U.S.A.) in 1980 or Mt Pinatubo (Philippines) in 1991. However, others (including the 2021 eruptions in La Palma and Iceland) are ‘effusive’: they involve massive lava flows, but no explosions. This difference turns out to be driven by the viscosity (or ‘runniness’) of the molten rock. When the viscosity is low, the lava flows easily, and any gases trapped within the molten rock can readily escape; if the viscosity is high the gas bubbles get trapped, until eventually they explode.

Satellite view (Copernicus Sentinel-2) of the Cubre Vieja volcano, La Palma, Canary Islands, taken on 30 September 2021. The behavior of lava flows, and more generally of volcanic eruptions, is determined by the viscosity of the flowing lava. This image has been processed in true colour, using the shortwave infrared channel to highlight the lava flow. Source: European Space Agency, Wikimedia, CC ASA 2.0.

Satellite view (Copernicus Sentinel-2) of the Cubre Vieja volcano, La Palma, Canary Islands, taken on 30 September 2021. The behavior of lava flows, and more generally of volcanic eruptions, is determined by the viscosity of the flowing lava. This image has been processed in true colour, using the shortwave infrared channel to highlight the lava flow. Source: European Space Agency, Wikimedia, CC ASA 2.0.

But viscosity itself is a puzzle: small changes in magma composition seem to have an disproportionately large impact on how the melt behaves. This is particularly true for magma erupted by ‘silicic’ (or silicon-rich) supervolcanoes like Yellowstone or Long Valley, and i-Melt points us towards an answer. Our results suggest that as the composition of silicic lava changes, their molecular structure undergoes a sudden transition, organising into a highly-connected network. This atomic connectivity makes the magma more resistant to flow, and it is this that creates a step-change in viscosity. While more work is required to fully understand the processes at work here, scientists at least now have an idea of where to look.

Perspectives

Following this successful proof-of-concept, we are extending i-Melt to a wider range of compositions, including oxides of magnesium and calcium that are important for both volcanology and glass science — work undertaken by Barbara Baldoni as part of an internship supported by the Data Intelligence Institute of Paris. Preliminary results will be presented at a meeting of the American Geoscience Union in December, and suggest that performance remains good. In addition to increasing the menu of ‘ingredients’, we hope to be able to include additional physical properties within our predictions. We also hope to exploit PyTorch’s flexibility to explore other machine learning approaches, such as Gaussian Processes — leveraging the capabilities of GPyTorch and Pyro.

Comparison between experimental measurements and predictions of the latest i-Melt model for various glass and melt properties. The new model integrates CaO and MgO, making it pertinent for the study of natural lava and industrial glasses.

Comparison between experimental measurements and predictions of the latest i-Melt model for various glass and melt properties. The new model integrates CaO and MgO, making it pertinent for the study of natural lava and industrial glasses.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sam Farahzad, Woo Kim and Mark Saroufim (Facebook) for their help with writing this blog post, as well as Aline Peltier (OVPF-IPGP) and Alexandre Fournier (IPGP) for pictures. This work is currently supported through a Chaire d’Excellence and the diiP, IdEx Université Paris Cité, ANR-18-IDEX-0001; funding from the Australian Research Council and the Carnegie Institution for Sciences is also acknowledged.

tags: